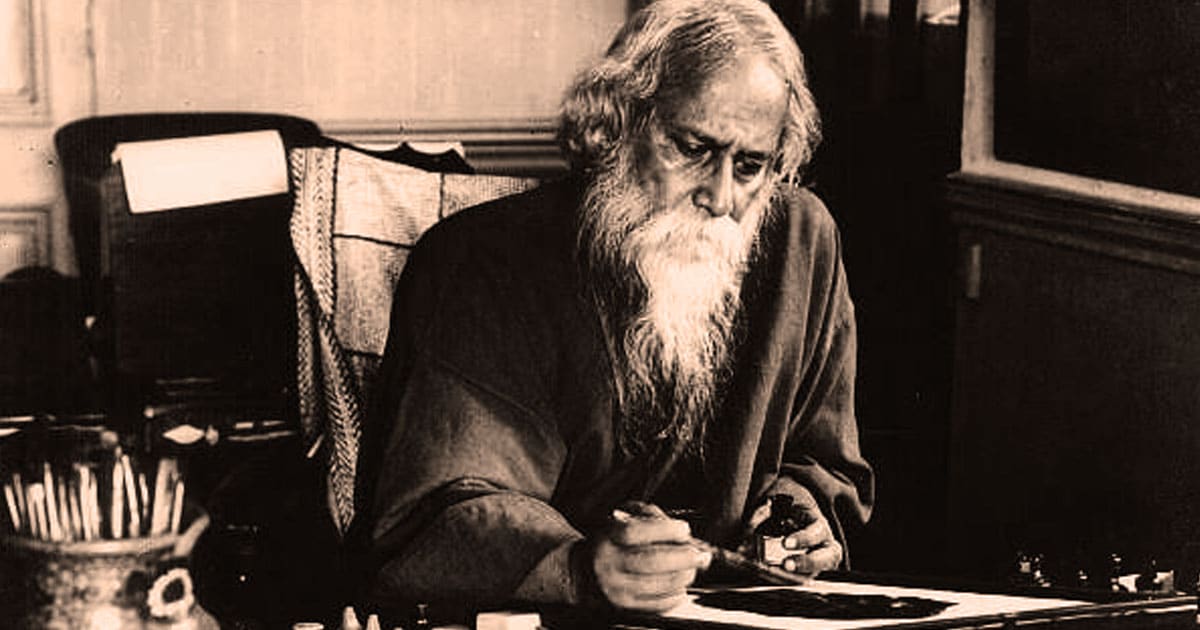

Rabindranath Tagore – the enormity of the persona needs no introduction. Rabindranath Thakur, as known in Bengal, given ‘Tagore’ is an anglicized version of the Bengali surname ‘Thakur’. Though frivolous, the trivia is worth mentioning in the heydays of him being appropriated beyond measure in the wake of the Bengal Assembly Elections.

From the repugnant parallels between him and the bearded Prime Minister of the country to him being invoked time and again while promising ‘Sonar Bangla’ (often being mispronounced as ‘Sunar Bangla’)- Tagore remained at the helm of relentless political propagations during the recent election campaigns.

The English calendar marks his birthday on 7th May of 1861. As per the Bengali calendar, it is the 25th day of the month of Baisakh and the Bengali year of 1268. This year, it happens to fall on the 9th of May, commemorating ‘Rabindra Jayanti’.

Growing up in a Bengali middle-class family, the day bears the nostalgia of the local club functions, to say the least. Needless to say, that sight was going to be remarkably different in the midst of a distressing pandemic. The commemoration of Tagore’s 160th birthday this year transcends all the glories of celebrations amid the flickering lights from the cremating bodies. It is the reality of grim and grief that marks the birthday- a birthday, where we turn the pages of his philosophy beyond the known tunes of Rabindra Sangeet and humming of recitable poetries. Perhaps, for this year, we take refuge in him to reinstate the passion for reason, the foundation of faith, and the belief in humanity.

Tagore was far from being the flagbearer of mainstream institutionalized education and rather is celebrated as someone who advents the breaking of barriers. Yet, his philosophical belief is closely mired in his dealings with scientific reasonings. One of his essays titled Manob Sarir (The Human Body), draws a parallel between the workings of the human body with that of society. Tagore says, “Human body is like a unified form of many governed subjects…every individual is a thousand alone, in fact, maybe more than that.” And yet, one ponders looking at the rallies of dead bodies in a pandemic-inflicted country that ‘each’ may not even count, that individuals are mere statistics, and that even thousands are standing alone in this amid the glaring state apathy!

While Tagore is often mentioned in the picturesque invocation of Bengal and his descriptions of nature, Tagore remains a devotee of love. Love, that often transgresses itself into the metaphysical with an amorphous existence of cosmos. For Tagore, love is often seethed in breaking norms, questioning institutions, and rearing humanity. Thus, Nandini’s ‘love’ in his 1923-play Raktokorobi (Red Oleanders) stands to signify an immortal resistance to repressive power and personify the metaphor of ‘freedom’. His quest for an ideal path of ‘love’ is beyond parochialism- an understanding that is significantly lacking among the contemporary political commentators of the country. But ‘love’, for Tagore does not stand apart as an abstract. In the form of its universalist approach remains the foundational principles of acceptance, embrace, and tolerance.

As the chest-thumping over temple-making rampages the country’s political discourse, countless human lives are being lost daily due to criminal negligence on the part of the ruling dispensation across the country. If the political commentators were aware of an iota of Tagore’s understanding, they would have known before appropriating him that for him temple resides in each individual as much as the whole universe is a temple of its own. And thus, institutions are nothing but extravagance. In one of his essays, titled Mandir (Temple), he writes: “The almighty is not farther from us, the almighty does not reside in buildings, S/He is omnipresent in all of us. The almighty is silently residing in all the lives and deaths, pleasure and grief, sin and saintly, union and departure. The universe itself is an eternal temple.” In the same essay, he bestows the unison of human existence with the glory of becoming God. He says, “The paternal, fraternal, familial, timeless, and historical unity becomes one, entangled in an almighty soul.”

Tagore, in his essay called Nabobarsho (New Year), envisages an India that seeks solace in its sage simplicity and its devotion to working alone, not expecting rewards. It is the same idea of work culture that even Bhagavata Gita propagates. But neither work of preparedness, nor simplicity- amid the pompous progression of the ongoing Central Vista Project, today’s India drifts further away from Tagore’s ideation. Yet, when a weary reader comes back to his/her Thakur (in Bengali, it also means God), Tagore does not let him/her down. Amid all the crises and despair, we see Tagore encircling us again with an idea of ‘love’- it is the love for humanity, it is the love for life.

He writes in his essay, called Monushyohtto (Humanity), “…the forms of human grief are diverse, it is deep, inexplicable even. The amount of grief in the universe is infinite. Yet, it is the same grief that makes human beings generous, it awakens human consciousness of the enormity of human extent, and it is in this enormity humans find happiness.” Thus, Tagore is an unequivocal celebrator of ‘faith’ in human existence. It is in the incessant social media SOS requests being responded to by fellow citizens, in the frontline workers being the real warriors, in the youth actively supporting people in the hours of need, that every loss of life amid the contagion becomes truly universal; that we tend to lose people as a collective; that we make grief perhaps a little more bearable.

When war looms, pandemic devastates or even famine comes, the human civilization is inadvertently faced with deep-seated crises and countless ambiguities. In 1941, in the middle of a raging world war and in the face of an imminent Bengal famine of 1943, an 80-year-old Tagore wrote one of his most memorable essays, titled Sabhyatar Sankat (The Crisis of Civilization). Even while the life of an infirm Tagore was receding, he firmly stood his ground in mounting a scathing critique of those in positions of power, yet clinging on to hope for the better days to come. Towards the end of the essay, he writes, “It is a sin to lose faith in Man…One day, an undefeatable Man will topple all the obstacles, progress towards exploring life, and gain his dignity back on the way…Today, let me tell you that even those intoxicated with the majestic power and arrogance will have to face an end to their adamancy”.

After all, it is not in the length of the beard, the wisdom resides. It is rather in his power of writing and nuances of thought that Tagore remains relevant. He provides solace to his readers in questioning the authority, seeking answers for people, and keeping the rays of hope alive. Had Tagore been alive, he would have lamented the defeat of justice, exasperatingly blatant in today’s India. Had he been alive, perhaps, he too would have been castigated as an ‘andolanjeevi’!