Every night Sorola Tudu could see the faint glow of light from the distant hamlet as she adjusted the flames of her kerosene lamp in her two-room mud house. The nights for the Santal Adivasis in the Gurusingpara village of Assam was as bright as the flicker of the expensive kerosene lamp.

Gurusingpara village in the Chirang district of Assam is an archetypical Santal village located just about 20 kilometers from the block headquarters. There are 104 households in this village, scattered over multiple hamlets; the majority of them belonging to Santal tribal group. One hamlet in the village has power connection but the supply is extremely erratic.

Ironically, the Champawati Dam is located just six kilometers from the village and supplies electricity to the Bongaigaon Refinery, some 35 kilometers away.

There is a song by the minstrels of Bengal, Bauls, urging the Santal Adivasis to migrate to Assam. The song eulogies the greenery and opportunity in Assam while lamenting at the fate of Santals elsewhere. The song was composed, possibly, after the year 1881, the first recorded year of the Santal migration to Assam.

The First War of Independence (1857), the great famine after that, the need for tea laborers and a plethora of other reasons are cited for the great migration. Notwithstanding the eulogies of the Bauls, the Santals in Assam remain one of the most disempowered and vulnerable groups. Like the Santal Adivasis in the rest of the country, they fall in the lowest strata of the social and economic pyramid.

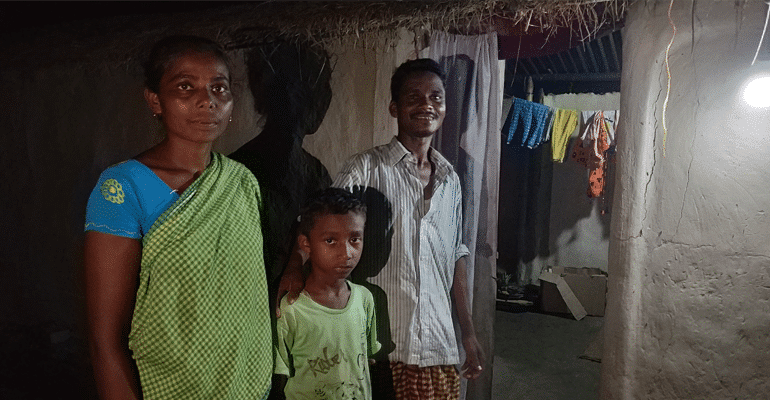

Sorola Tudu’s two-room mud house serves two purposes: storeroom for grains and living quarters. Five months back, her family depended on expensive kerosene lamps at night.

“At times, it got so dark outside that I was even scared to do the dishes”, she says solemnly.

“We have been waiting forever for the authorities to come and light our village”, adds her husband Matla Hembram

But given the remoteness of the village and the complete lack of accessibility, there were no easy solutions on offer.

When NGO SeSTA(Seven Sisters Development Assistance) and Selco Foundation came together to resolve this issue using solar energy, there were only a few takers in this village. An easy loan based solar home lighting system seemed feasible yet a distant reality. No one had seen an arrangement of this nature.

The farmers of this village itself are part of a Farmers Producers Organisation, promoted by SeSTA. SeSTA has been working here on improved agricultural production and natural resources management. After several rounds of the community meeting, the first lighting system was set. Within a month, 18 more houses were brightly lit at night, by the energy of the day.

Ram Tudu says, “I don’t have to travel for two kilometers just to get my phone charged.”

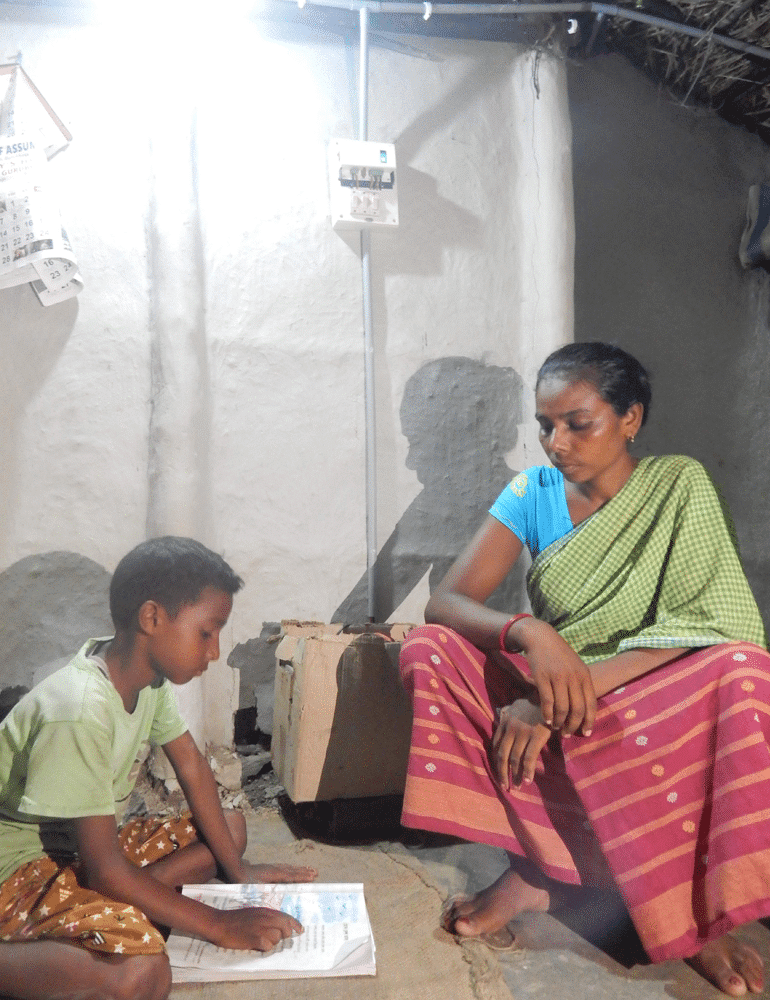

Sorola smiles as her son Mitha is engrossed in a book under the light of a bulb, powered by solar energy.

“In the last four months, I have stopped shouting at him to read, like our kerosene days”, she says with a smile.

“It is stress-free to do the dishes now at night or cook. Solar lighting has made my life easy. I am planning to buy a sewing machine and use it at night, after finishing my work. I have got training for sewing through a voluntary group last year and want to use that skill to increase my income”, she says, exuding in confidence.

All the 19 houses in the area have the same story. In some way or the other, solar power has radiated their lives. And one can’t help feeling that this is just the first step- the conquest of the dark in this remote village by the Santhals, using the power of the sun.

The eulogy of the Bauls may, perhaps, come true, one day. Or one brightly lit night!