“Pehle se hi toh hum mar-mar ke aur chhup-chhup ke jeete the, abhi toh Covid-19 ne aur bhi maar dala. Sarkar ke taraf se lockdown khul gaya hoga par hamare zindagi pe lockdown abhi bhi laga hua hain” (Even prior to Covid-19 we were living under dire conditions and in secrecy, the pathogen has pushed us even further to the edge. The lockdown may have been lifted by the government but our lives are still under lockdown) – told by one of the members of the sex workers community, succinctly captures the holistic reality of the contagion in the lives of the sex workers.

The heart-wrenching images emanating from the lives of daily wage laborers are neither new nor unusual amid the past 5-months of lockdown phases, aimed at controlling the contamination of Covid-19 pathogen. While the issue received considerable attention, a section of them involved in sex work, forming one of the strongholds of India’s unorganized economic sector (92% of Indian workforce constitutes the informal/unorganized sector), has not been spoken of enough.

Broadly defined by universal standards “as a contractual arrangement where sexual services are negotiated between consenting adults”, sex work (traditionally known as ‘prostitution’ owing to the connotations of ‘immorality’) is among the oldest professions thriving on earth. A profession that is old enough to find its references even among the ancient Indian literature including the Vedas and Arthashastra.

Even though the unofficial figures may render higher, according to a 2016 report by UNAIDS there are approximately 6.58 lakhs sex workers in India, though National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) has claimed to have registered over 8 lakhs sex workers in the country in 2009. In India, the network includes a broad ambit of brothel dwellers, home-based service providers, part-time domestic and other daily wage laborers, escorts, and, masseurs to name a few, and all combined the number may go up to 3 million.

A study of sex work, published in 2014, based on the findings made in 14 states across the country discovered that over 50% of female sex workers had previously worked as domestic help, construction laborers, and daily wage-earners, while at least 30% of them continued taking up these simultaneously with sex work.

The societal scorn towards the profession played a major role in relegating the sex workers, largely women, and other sexual minorities, into further oblivion amid the Corona pandemic. While difficulties amidst the situation were not unexpected, probing deep into the reality exposes the darker truths of marginalization within the community, especially pertaining to the issue areas of livelihood, sanitation and healthcare facilities, and stigmatization.

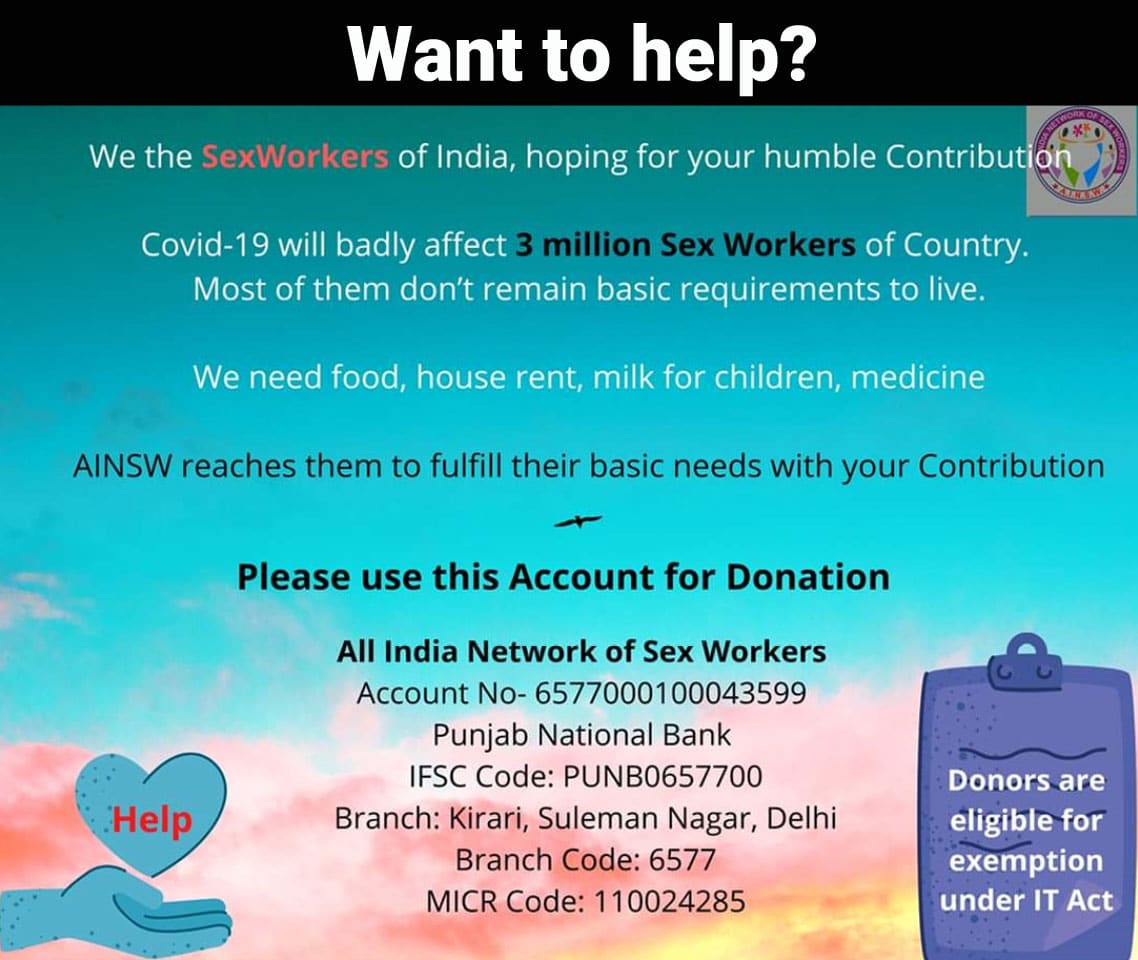

Over exclusive conversations with LifeBeyondNumbers, Kusum, the President of the All India Network of Sex Workers (AINSW) and Sultana Begum, Secretary of the Community based organization (CBO) Sarvodaya Samiti shared their valuable insights and glimpses of experiences over the state of these workers in Delhi’s GB Road and Rajasthan’s Ajmer respectively.

Loss of livelihood

With absolutely no means of earning, the sex workers of the country faced one of the most calamitous phases of their lives during the lockdown. The official numbers of the sex workers residing in Delhi’s GB Road are approximately 5,000.

Since none understood at the beginning for how long the lockdown is going to sustain, most of the sex workers, based in GB Road, stayed back in their respective brothels expecting the situation to have gotten improved soon, while the home-based workers both in Delhi and Ajmer anyway had no option in hand.

Thus, not only were the brothel-based sex workers stuck, unable to go home in the middle of it but also in general, sex workers were unable to make their ends meet and pay the due house rents. The ones who had their villages to go back to were not even allowed on certain occasions to leave without making advance payments of their house rents.

“The workers staying in Delhi’s brothels are under huge pressure primarily due to their unpaid rents. Additionally, with no work in hand they are also inept in buying the regular essentials which include groceries, medicines, and sanitation products,” says Kusum.

Prices of everyday essentials rose extensively during the initial phases of the lockdown and chunks of the savings made by these workers had to be spent merely for buying groceries and vegetables. Even when certain NGOs have been making dry ration available, with empty gas cylinders in brothels, they are of little to no use. “There was not even enough money to buy milk for making tea,” laments Kusum.

“Certain NGOs did distribute cooked food for the impoverished in general, though it did not specifically mean for sex workers. After days of starvation, one can understand the desperation among people to grab the cooked food. The cooked food used to get over within half an hour and many including sex workers in the area used to remain left out,” Sultana Begum explains the dreadful situation that the workers in Ajmer faced. The supply and demand ratio of such distributions was starkly skewed.

The situation was so dire and the scarcity so deep that Sultana Begum along with a few more workers started collecting stale vegetables that were to be thrown out otherwise, from the vegetable vendors and distributing those among the sex workers after cleaning those with fresh water.

“We used to go to these vendors at 5 in the morning and collected almost 2-days old half-rotten vegetables from them. Even for oil and salt, we used to collect some from the relatively well-off people in the areas and give away a few grams to each for surviving at least for the time being. I used to break down myself while giving away stale vegetables to them as they never had seen such difficult days as a part of the profession”, Sultana’s voice choked while elaborating on it.

Reshma (name changed for anonymity) working in Rajasthan’s Ajmer could not bear seeing her children starving for consecutive two-days and ventured out for work amid the peak of the lockdown in exchange for merely Rs.1000. While being rebuked by the other members of the community for risking her life, she bluntly said: “We will die of starvation first, much before getting infected with Covid-19”.

“We cannot bear seeing our children begging for food anymore. If we die of Covid-19, at least our children will get two-times food in the orphanage,” Sultana recalls some workers giving her the reasons for restarting the work. A perplexed Sultana had no better way to reassure them and stood still in front of the teary-eyed workers.

Neha (name changed for anonymity) another worker in her 30s had to sell whatever valuables she had to arrange money to somehow send her children of 6 and 12-years-old to her mother’s place in UP. “A mother who involves herself into the profession for their children had to send them away from her. What else can Covid-19 take away from us?” asks Sultana.

Even when the unlock phases have begun, sex workers are still majorly out of work. Due to the dearth of available means of earnings, some of the workers in Delhi’s GB Road are forced to restart working recently despite major risks.

The economic migrants staying away from their respective houses formed one of the largest clienteles for the sex workers across the country’s big cities. As most of these migrants were forced to return home amid the pandemic lockdown, sex workers in the big cities have lost chunks of their client base. The risk of contagion has worsened the situation as both the clients and the service providers are unable to gauge the risks of intimacy.

When asked why are they exposing themselves to grave risks of Covid-19 infection, the invariable answers had pointed to the unbearable economic conditions. “We have been keeping ours and the client’s masks on during the intimacy and after intercourse, we sanitize our bodies with the chemical sanitizers,” one of them told Kusum. A perplexed Kusum asked her “Why do not you take bath right after?”. “There is ample scarcity of water, a dearth of soaps, and inadequate opportunities to take bath every time after the intercourse” the anonymous worker pointed towards the abysmal sanitation condition in these Delhi brothels.

Kusum realized that the sanitizers distributed among the workers by several NGOs are the quick resorts for them before they go on attending other clients. Though both Kusum and Sultana attempt their best to induce awareness among the workers regarding sanitation, even they cannot fully ensure all the workers to be following these protocols in toto.

While at least the sanitizers and masks were made partially available for the workers by the NGOs in the national capital, the workers living in the small town of Ajmer did not even receive a sufficient number of health kits. The members of the community themselves sewed masks out of their old sarees and distributed those among themselves as well as those exposed to high risks.

“Distributions of health kits that were happening in pockets were turned into gimmicks by small political leaders. All they were doing in the name of philanthropy was to distribute masks among the dwellers of particular lanes and posting it on social media for seeking publicity,” says an agitated Sultana. Though people and private organizations were taking efforts in individual capacities, hardly consolidated efforts were put forward on the part of the authorities.

“Lockdown is still persisting in our lives, despite the beginning of the unlock phases. While the risk of infection remains inescapable, given that in Ajmer sex work is not organized under brothels, from daily means of commute to finding appropriate places/houses like hotels, guesthouses, dhabas, restaurants, etc. for the conduct of the work are scarce under these circumstances,” Sultana elaborates on the challenges faced by the Ajmer-based workers. Even the permanent clients of these workers who had made lofty promises to the workers had stopped receiving their calls as they themselves are facing the brunt of the economic slowdown.

As the unlock phase began and the Prime Minister’s mantra to relax rent-collection during the lockdown vanquishes, the house owners have started demanding house rents and electricity bills from the workers while still there is no work available for the sex workers.

Amid the lockdown itself, in Ajmer, Razia (name changed for anonymity) was thrown out of her house, and for the next 15 days, she rendered homeless along with her three children. For any new place that she was seeking, advance deposit money was demanded which she had no way to arrange.

In Ajmer, one of the sex workers had, in fact, committed suicide by hanging due to the soaring amount of debts on her that she failed to pay back. She was also being blackmailed by the moneylenders on the ground of revealing to the world her engagement with the profession. “Woh toh jaake bacch gayi, (She got freedom in death)” Sultana Begum sighs remorsefully.

Administrative Mismanagement – Cry over documentation

Most of these workers living away from their home-towns and amid an already appalling state are largely undocumented with no identification cards with them, while the government schemes are usually directed towards people with adequate documentation. Of course, these generic government schemes, that allotted a total of $22.5 billion relief package, are meant for everyone fulfilling the economic criteria. No specific scheme has been promulgated for the sex workers.

“Even the ones with some identification cards like birth certificates, voter ID cards, Aadhar cards, etc. do not have their documents in the right condition and properly updated or have address discrepancies and unrecognizable photographs,” explains Kusum. Especially, sex workers in their late 40s and 50s face major challenges in this regard as after leaving homes at tender ages they have been staying in these big-city brothels for years.

Among the many materials facilitated by various organizations in GB Road are dry ration, nutrient products for children, masks, and sanitizers, and sanitary napkins. Private organizations have also managed to send money to over 500 account holder sex workers in several parts of the country.

In fact, for years organizations like AINSW are trying to get the documentation that includes birth certificates, caste certificates as well as other identification cards through their ‘single window programs’. Despite attempts, many workers operating in Delhi’s GB Road were largely left out of its ambit.

The situation was all the more difficult in Ajmer where the government scheme that promised 5-kgs of dry ration for the impoverished, sought active ration cards linked with the Jan Adhaar cards against each of the recipients. Recipients had to show the One Time Password (OTP) received on their linked phone numbers specifically for availing the facility. Quite obviously, not all the sex workers having ration cards had their cards linked both due to unawareness and unpredictability of the situation.

Even the Central Government scheme of Jan Dhan that promised to put Rs.500 in each Zero Balance bank account was irregular. Many accounts belonging to the members of the community were in fact deactivated due to non-usage and some could not even manage to get the Zero Balance accounts open. “When the members of the community took their appeals to the District Administration of Ajmer, they were informed that the funds available to the administration are allocated for urban development and not for conducting relief works,” tells Sultana.

A dearth of alternative means of earning

Due to the precarity of the situation, there are hardly alternative modes of earning available to them. At most what they could have looked for are working as daily wage laborers in the nearby industrial areas, domestic help, beauticians, etc. The chance of getting through these opportunities has been rather slim for the sex workers as the lockdown has taken a significant toll on the sector. Even the ones available earn them too little to lead a minimalistic life as opposed to earning between Rs.500 and Rs.1000 daily through sex work.

“The government approach towards supporting the sex workers is usually translated in terms of rehabilitating these workers, attached and experienced in sex work for years, and redirecting them towards different skill-sets,” says Kusum.

On the presumption of changing the course of the profession into learning novel skill sets, these rehabilitation programs attempt at enabling them in sewing, cooking, handicrafts, etc. which pay them nominally and keep up with the state-centric standardization of ‘dignity’, closely adhered to the values of ‘acceptable feminine work’.

There is no scheme that looks for empowering them within the purview of sex work due to the state aversion towards the profession. “Sarkar ki soch achaar-papad ke aage badhta hi nahin” (The government does not think beyond inducing the skills of making pickles and snacks among the sex workers), says Kusum.

Rehabilitating the sex workers in their 40s into learning new skill sets without trying to come up with effective solutions towards their everyday problems is one of the most problematic aspects of the administrative approach towards the matter. The rehabilitation centers are in fact not well-equipped with maintaining the demand-supply chains and adequate marketing of the products.

“We would seek for alternatives only if it goes at par with the sex work, not by leaving it altogether. Most of the sex workers are into the profession by choice and due to the relatively higher income that it allows in comparison to other works in the unorganized sectors to avoid abject poverty,” explains Kusum.

While reports suggest city-based young female sex workers are resorting to the means of technology-based apps like WhatsApp and Google Pay for continuing work from home virtually through the modes of video calls and digital payments, not enough takers of it are available as the clients themselves hardly have provisions to pay for these virtual services. Though in most of the cases, the faces of the workers are concealed, leaving such digital footprints may expose them to unknown vulnerabilities related to identity revelation.

Lack of sanitation and health care facilities

Most of the sex workers are at a high risk of contagion. Apart from the fact that these workers deal with co-morbidities like blood sugar, hypertension, hepatitis, and HIV, the entire community is also exposed to greater risks of manifold infections due to unhygienic conditions in the brothels and lack of healthcare facilities.

Workers in need of daily dosage of medications are running out of it and new medications are difficult to avail. The means of clinical abortions have also shrunk drastically. These are largely due to the fact that most of the government healthcare facilities have now channelized all their efforts into fighting coronavirus and the attainment of public health care for communities as marginalized as the sex workers have been harder than ever.

“Primarily, for the initial three-months, there was absolutely no means of conveyance available for these workers to even avail healthcare facilities of any kind. Even when they knocked the doors of government hospitals after providing them with minimal health care, the hospital authorities have shown reluctance into admitting non-Covid patients to avert the risks of infections among the new patients,” Kusum points out.

In Ajmer, they have also reportedly been denied treatments on multiple occasions. The only option that is left to them during emergency situations is to go to the private clinics, though many are even avoiding the same as it involves spending a hefty amount of money.

When one of the members of the community passed away due to the Covid-19 infection, members of the community living in the same lane as hers in Ajmer were initially denied tests. While after efforts the tests were conducted, the authorities denied furnishing the ‘negative’ reports.

The abysmal state of sanitation conditions among these brothels is not new. Due to the lockdown, it has worsened further. Apart from the fact that there is a dearth of cleaning in these brothels and adjacent localities, products for sanitation that include soaps and phenyls are not readily available.

Police harassment

While the cases of police harassment against the sex workers in the pretext of alleged unlawful solicitation and public obscenity are not unheard of, the fear of Covid-19 has aggravated the situation further.

Around the brothels in Delhi, even when the sex workers had been descending downstairs to avert the heat or to go out for buying regular essentials, police personnel immediately came up to them and sent them back to their respective places in the presumption of these workers making solicitation attempts.

The ones trying to get out of their houses for availing healthcare facilities were also not spared on certain occasions in Ajmer. Without bothering to know the reasons behind these workers going out, they were thrashed and fined indiscriminately for not wearing masks.

In Ajmer, a handful of sex workers tried selling door-to-door vegetables after making contact with the big vendors. They were mercilessly thrashed by the Police for installing those small movable stalls of vegetables and their stalls were vandalized.

“Ajkal randiya bhi sabzi bechne lag gayi! (Prostitutes have now turned into vegetable sellers)” is how they were mocked at by the police. After needful interventions made by Sultana Begum and her team, eventually, the authorities have designated a particular place for installing their vegetable stalls.

The stigma attached-law and colonial morality

Historian Ashwini Tambe’s analysis of the Contagious Diseases Act of 1868, Mumbai, explains how the colonial morality seeped into the Indian psyche as it turned the city-brothels into the ‘house of ill-fame’ responsible for moral corruption and contamination. While it pushes these workers into darker seclusion, their rights to a dignified life are virtually denied.

Governed under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, sex work in India though is not illegal per se, associated activities such as the establishment of organized brothels, solicitation of clients as well as the conduct of sex work within the 200 meters radius of public spaces including hotels, guest houses, and restaurants are punishable by law. The law also prosecutes adults making a living out of sex work.

The act operating under the Victorian morality dubiously implies sex work to be done individually yet away from public spheres and hence, practically turns it into an ‘open secret’ with no means of the workers to exercise their legitimate right to work.

Provisions like this further accentuate the inability of the sex workers to seek access to justice and legal remedies in the face of abuse and exploitation in the hands of brothel owners, pimps, customers as well as family members. Neither does it support workers who are unlawfully trafficked and forced into sex work as it technically traps trafficked victims into prison-like ‘protective homes’.

An analysis of cases in 22 High Courts of the country between 2010 and 2013 reveals about merely 8 cases related to the myriad realm of sex work. This awfully low number is indicative of the inaccessibility of recourse to justice for these workers.

Moreover, the Epidemic Diseases Act,1897 in tandem with the National Disaster Management Guidelines, 2008 pertaining to the critical management of biological disasters makes no reference to safe evacuation and relief of marginalized communities, including that of sex workers.

A new modeling study, published in May 2020 and conducted by the researchers at the Yale School of Medicine and Harvard Medical School, seemed to have suggested restricting the country’s red-light areas in the pretext of these areas becoming the hub of contagion. It suggests restricting commercial sex work in cities like Mumbai, Kolkata, New Delhi, Nagpur, and, Pune during the lockdown and thereafter the study has claimed to have found the chances of reduction of the rising Covid-19 cases by 72%.

The study seemingly stemming from the deep-seated prejudices, not only is negligent of the precarity it induces in the lives of millions of sex workers in India but also suggests no measure to reform the ground-conditions. While no single attempt has been made to test the workers in these brothels for Covid-19, the projection of brothels posing greater risks of infection is tied with the inherent stigma attached to the profession.

“If the attempt is to shut down brothels, I am certain that it cannot stop sex works from happening across the country. The more the attempts of de-legitimization of the profession, the more the chances of sex work happening undercover and in secrecy. As it goes undercover, tracking down on the unlawful activities and infections within the profession will get next to impossible.” foresees Kusum resolutely.

Needless to say, during the rapid spread of HIV, the networks among the sex workers have worked together in gaining awareness and not attending the clients unwilling to use condoms. The overall outcome of their efforts has been the containment of HIV infection to a large extent in the country.

“Persons selling sex in India belong to the vast population of informal sector workers and migrants whom the state has spectacularly abandoned at this time of lockdown and crisis,” opines Shakthi Nataraj. While the prejudices against the profession are rooted deep inside the Indian psyche, the voices of the community members are put to silence when it comes to formulating policies for them.

At the end of the talks with both Kusum and Sultana, all they had to ask for is ‘help’. While all the write-up could have attempted is to reveal the perilous situation of India’s sex workers, their plead stayed pervasive. After all, not even an iota of their experiences can be shared and feelings can be felt by ‘us’, the armed-chair writers!

* A special thanks to Mr. Amit Kumar, the National Coordinator of AINSW, for connecting the author with Kusum and Sultana and adding his valuable insights to make the research worthwhile.