What to do if you want to help people in need? First, educate yourself about the issues you want to focus on, understand them and then act on those problems. This is exactly what a woman from Thane, Maharashtra has done. And what makes her one of the strongest women? Her ability to stand with the migrant workers and help them to live a dignified life.

In a conversation with Life Beyond Numbers, Rupal Kulkarni (32) who is the CEO of Shram Sarathi says, “Our vision is to bring security and dignity to the lives of migrant families and help them escape a life of bondage.”

Shram Sarathi – The Begining

Currently headquartered in Udaipur, Shram Sarathi is the brainchild of Rajiv Khandelwal, who while working on development projects in rural Rajasthan realized that most young men were missing from the villages and were working as migrant labors in Ahmedabad, where they were working in precarious conditions.

Unable to bear this, Khandelwal conducted a joint study with UNDP on the magnitude and nature of migration from Rajasthan. The findings of this study prompted Mr. Khandelwal to establish Aajeevika Bureau and eventually, Shram Sarathi to build a systematic response to the issue of distress driven migration from the region.

Shram Sarathi began its operations in 2009 and a year later, Rupal was introduced to the initiative through the ICICI fellowship (now known as the India Fellows Program) and what inspired her to continue was the excellent work culture, a clear focus on client welfare and the openness to innovation.

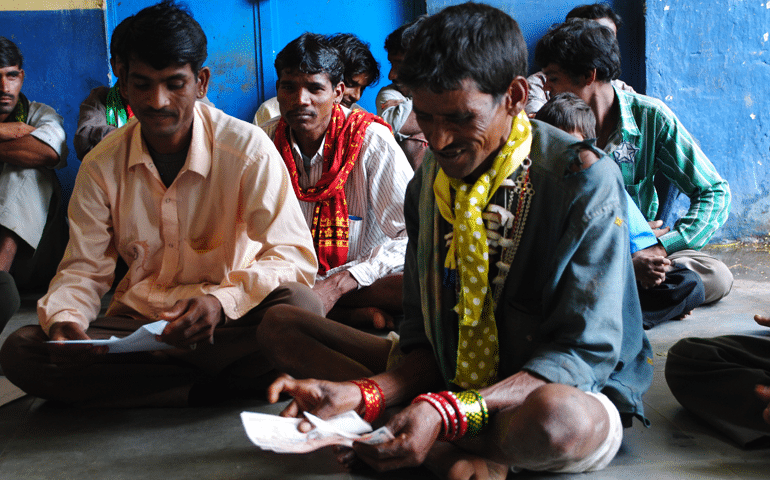

Rupal has been associated with the organisation for 10 years and says, “The problems crept in for these workers when prior to embarking on their migration journey, most workers took an advance from their contractors, which often lead to a perverse labour contract of pledged labour against cash advance, reduced wages and fraudulent payment deductions.”

The Problem In Focus

Many of these migrant workers are forced to save their money with their contractors or local ‘Kirana’ stores, and it comes with a cost. During the male absence, left-behind families experience severe cash flow volatilities and are compelled to borrow from local moneylenders at rates as high as 5-25% per month.

Given the mobility of this group, banking institutions perceive them to be a highly risky group to lend to and they are therefore excluded from affordable credit services both at source and destination. Furthermore, such households have poor cushioning from risks such as death, disability, illness and old age. Few workers have access to any social security measures such as insurance and pension.

Notably, the economic life cycle of workers is significantly reduced – an entry into the labor market at a tender age of 13-14 years usually leads to an early return. In most cases, these households slide back into poverty with limited or no savings. In the absence of access to formal financial services, migration for this group of workers fails to be an accumulative and positive economic opportunity. Therefore, Shram Sarathi was established to address these challenges by working on the financial inclusion of labor migrants and their families.

How Shram Sarathi Is Solving The Problem

Shram Sarathi works on financial inclusion of highly vulnerable labor migrants and their families and offers a comprehensive suite of financial services that are uniquely designed and delivered to migrant families. These services include credit, savings, insurance, pension, and remittances. Apart from that they also have a financial literacy program with a strong focus on wage-related literacy.

The organization operates from branches that reach remote rural locations in four districts of south Rajasthan (Udaipur, Rajasamand, Dungarpur and Pratapgarh districts) and also has a presence in Gujarat and Maharashtra. “While most institutions perceive migrants to be a very risky customer segment, it is our belief that with the right product design and the right delivery channel, migrants are just as credit-worthy as others. Our work on the ground has demonstrated this,” says Rupal.

Through this initiative, they ensure that migrant families have access to affordable, reliable and appropriate financial services. “Some clients report that having access to timely credit has helped them escape a life of bondage and while others have improved agricultural productivity, diversified incomes through local businesses and tided over health emergencies,” she says. Further, the workers also report that the ‘distress’ associated with migration has reduced.

The organization has designed a housing product that helps workers save about 2 years in construction time and reduce the cost of construction by 100%. Moreover having a complete house also helps them make more informed choices on where to migrate and how long to migrate for.

On asking how working for these labors and understanding their problems helped her grow as a person? Rupal says, “There are several lessons we have learned over the years working on the financial inclusion of migrants. Popular discussions on financial inclusion of migrants usually center around remittance services, however, it is important to recognize that a more holistic wealth management approach is essential to the financial inclusion of migrants. This includes offering instruments that help manage erratic cash flows, cope with risks and accumulate wealth. It is equally important to situate financial services for migrants in the context of informality, poor living and working conditions and risky jobs.”

Adding to this, she mentions that through their work, they have learned that providing access to finance for a host of other needs is central to reducing vulnerabilities and often helps generate additional incomes as well. For instance, their impact assessment studies have demonstrated that housing finance services that help a migrant family complete the construction of a pakka house can increase annual incomes by up to 12,000 rupees for the family.

Therefore, Shram Sarathi offers micro-loans for various financial needs such as the construction of a house, agricultural investments, tiding over health emergencies and freeing up mortgaged assets such as land and silver by repaying moneylenders, in addition to financing local enterprises.

The problems are not restricted to men, women too face multiple challenges in the labor market and wage discrimination is one of them. “Their wages are usually lower than that of their male counterparts for similar work. Women are also usually relegated to unskilled jobs across various industries like construction and transportation and have little encouragement to advance their skills,” says Rupal. What’s worse? Women’s work in the household, looking after children and the elderly, their work in farms, tending to cattle and others- the sad part is these are not recognized as ‘work’ and hence they are either unpaid or undervalued.

In the absence of the men, who migrate, women face additional challenges at source (i.e. the villages where they live). For instance, women from migrant families tend to have lower creditworthiness, even among informal moneylenders. As a result of this in case of emergencies when the men are away, they usually avail informal credit at very unfair terms. Similarly, in the geographies that we operate in, women typically do not have ownership of mobile phones and even find it difficult to access formal banking channels.

Migration in Rajasthan often begins at a very early age and there is a popular saying in the region: “Pass hue to zindabad, fail hue to Ahmedabad”.

Children usually drop out of school around the age of 12-13 years and begin migrating for work. Due to a lack of skills, they usually engage in physically demanding jobs. By the age of 35-40 years, they are physically exhausted and unable to sustain long hours in unskilled jobs. As a result, the cycle of early migration often repeats itself and a new generation starts migrating at a very young age. In the absence of any interventions, abject poverty often compels young children to migrate and contribute to household incomes.

There is a general dearth of reliable national data on migration and labor. Several civil society organizations and researchers are now, however, working on the subject and building valuable knowledge resources on labor migration in the country.

“Shram Sarathi has several partnerships in the industry. These include partnerships for provision of services such as insurance, pension, remittances, and savings. We also have donors and lenders who support our vision to bring security and dignity to the lives of migrant families,” she adds.

Since its inception, over 15,000 migrant families have directly accessed financial services and we have reached nearly 50,000 workers through our financial literacy program.

If you are looking for a way to help people in need but lack inspiration in any form, just remember what Saint Teresa once said, “I alone cannot change the world, but I can cast a stone across the waters to create many ripples.”